Several internet posters have determined that he was the son of Hans Martin Keller (1682-1732) and Margretha Loscher (1684-1737) who were married 14 January 1698 in Schwaigern KB, Weiler, Germany. Their son Carl was born 14 April 1702 according to church records.

Immigration to Lancaster County, Pennsylvania

Although a Charles Keller appears on a list of pre-1730 settlers in Lancaster County, it isn’t clear that this was the same person, as his name appears under the heading “1719”, presumably meaning the year of the list. 1

He is believed to have been the same person who arrived in Philadelphia on 5 September 1730 on the ship Alexander and Anne from Rotterdam by way of Deal. The captain’s manifest, listing 46 male Palatines above the age of 16, along with 84 unnamed women and children, lists him as “Charles Kallar”. He signed both the oath of abjuration and the oath of allegiance on the same date in German as “Carl Keller”.2 He apparently Anglicized his given name to the English “Charles”. (Note that the Latin form of the name is “Carolus” and the German form is “Carl”.)

He was apparently the first of his family to arrive in Pennsylvania. His brother Johannes, and perhaps his mother, along with his first cousin George Keller arrived in the ship Pleasant on 11 October 1732. He and his mother Margaretha were sponsors in the First Reformed Church in Lancaster in 1737. 3

In 1738 a number of German immigrants living in Lancaster County were naturalized by an act of the Pennsylvania General Assembly, among them a “Charles Keller”. 4 Oddly, there is no record of a deed to or from Charles Keller in Lancaster County.5

Naturalized again in 1747

On 4 August 1747, at a court held for Frederick County, Virginia, “George Keller a German Protestant, having made it appear to the court that he has been an inhabitant of this colony seven years and not absent therefrom two months at one time during the said term, and having produced a certificate under the hand of the Rev’d. John Bartholomew Rieger that he hath received the sacrament of the Lords Supper as the Act of Parliament directs to be taken instead of the oaths of allegiance and supremacy and the abjuration oath & subscribed the test in order to obtain Naturalization, the same is admitted to record.” 6 Rev. Rieger, who provided the certificate, ministered a church in Lancaster county, Pennsylvania. Keller may have sought a local proof of citizenship in order to obtain land in Virginia.

The Move to Virginia

By the late 1740s he was living on the frontier a considerable distance to the southwest in what was then Frederick County, Virginia and is today Mineral County, West Virginia.

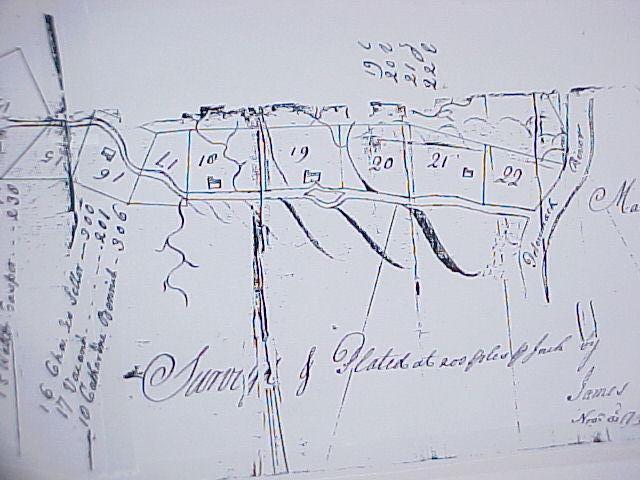

By 1747 about two dozen families had settled along Pattersons Creek, a fifty-mile long creek emptying into the north branch of the Potomac River. In early 1748 Lord Fairfax employed James Genn, a surveyor of Prince William County, to develop a survey map of the settlements preparatory to the issuance of land grants. Genn produced his survey in November 1748 — a portion of which is reproduced below.

Charles Keller’s survey — known as Lot 16 — was 300 acres on both sides of Pattersons Creek surveyed in November 1748. 7 The plot was known as Lot 16 and was bisected by Pattersons Creek about four miles up the creek from the Potomac River and roughly at the location where the local road alongside the creek turned west toward what would later be Fort Cumberland. He never completed the grant process but the land was finally granted in 1779 to his son John Keller.

James Genn’s 1748 survey of lots along Pattersons Creek shows a cabin on Lot 16, on the east side of the creek, which apparently housed Charles Keller and his family. (Note that the map faces roughly west, as Pattersons Creek runs more or less northward into the Potomac River. The other side of the river is Maryland.)

A road order dated 8 August 1749 lists forty residents, among them Charles Keller, had petitioned for a road to be built “from the lower part of Patterson’s Creek by Power Hazels [Lot 8] into the wagon road which leads from the [Winchester] Courthouse to the South Branch [of the Potomac].”8

Fort Ashby erected at “Charles Sellar’s Plantation”

The French and Indian War (1754-64) made the frontier a dangerous place for settlers and the Patterson Creek area was subject to numerous Indian skirmishes that killed or drove away most of its residents by 1757. The correspondence of George Washington during the French and Indian War regarding forts on Pattersons Creek mentions Charles Keller several times — but as “Sellers” rather than “Keller”. (The reason for this is unclear. Examination of the original handwritten documents clearly shows the name written by multiple authors as “Sellers”.)

On 23 October 1755 Washington wrote to Lord Fairfax’s nephew George William Fairfax to report that he had ordered Captain John Ashby’s company of rangers to remain “at Sellars’s” and Captain Cockes’ company to remain at Nicholas Reamers to “protect the Inhabitants on those waters and to escort any waggons to and from Fort Cumberland.”9 Three days later Washington wrote to Allan McLean to order provisioning of “Captain Ashby and company at the Plantation of Charles Sellars.”10

He wrote to Lt. Richard Bacon of the independent Maryland company on the same day to order the building of two forts, one at George Parker’s plantation and the other “at the Plantation of Charles Sellars or the late McCrackins; whichsoever you shall judge the most convenient station.” 11 The following day he wrote to Captains John Ashby (“stationed at Sellar’s and McCrackins”) and William Cocke (stationed at George Parker’s plantation) informing them of the orders.12

Both forts were to be ninety foot square palisades with bastions, but Washington later instructed Bacon that the forts were “only intended by way of cover to the Rangers, and as a receptacle now and then for provisions [and therefore] you are desired not to plan any work, which requires much time to execute. We have neither men or tools, to carry on the undertaking with vigour.”13

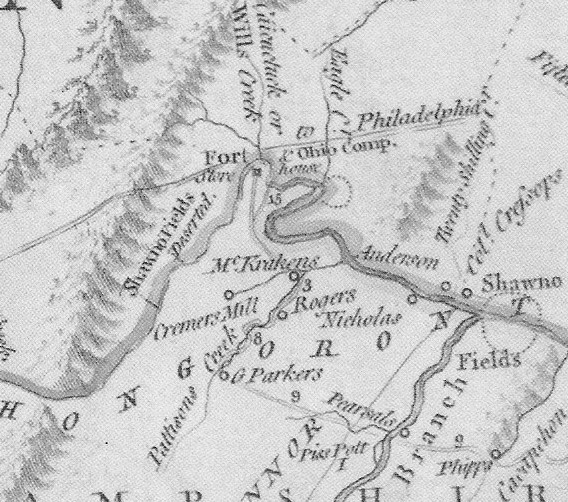

The two forts can be clearly located thanks to Genn’s 1748 survey and a 1754 map. The Fry-Jefferson map of Virginia (see below) which surveyed the area sometime in 1754, before the forts were built, shows “Pattisons Creek” running northeast into the North Branch of the Potomac River. Sellars plantation is not shown on the map, but McKrackens (on Lot 17) and George Parker’s plantation (on Lot 1) are shown at key points on the roadway from Winchester that turned down the creek before heading west to Fort Cumberland. James McCracken had been killed by Indians in late October 1755 but Charles Keller (“Sellars”) was evidently alive when the forts were constructed.

The “Fort” on the map is apparently the predecessor to Fort Cumberland. In the lower right is the site of Fort Pearsall on the South Branch of the Potomac. There was also a small fortified storehouse at the mouth of Patterson’s Creek on Lot 22, which has sometimes been erroneously referred to as “Fort Sellers”.14 Just off the map was another fort called Fort Keller located in what is now Shenandoah County.

On 29 December 1755 and again two weeks later on 12 January 1756, Lt. Thomas Rutherford submitted a roster of Captain Ashby’s 2nd Company of Rangers “stationed at Sellers’s Plantation on Patterson Creek”, showing that the garrison numbered only about 25 able-bodied men owing to disease and desertion. 15

On 15 April 1756 Ashby reported that 400 Indians had demanded the surrender of his fort, while another party of Indians attacked Cocke’s garrison further up the Creek. 16 Washington ordered both forts strengthened by an additional 21 men.17

By mid-1756 the fort was routinely being referred to as “Fort Ashby” or “Ashby’s Fort” rather than as Sellars Plantation. That may reflect the death of Charles Keller and his family’s removal from the area. The final mention of Charles Sellars in the Washington papers was on 1 August 1756, when Col. Adam Stephen wrote to Washington from Fort Cumberland, mentioning the garrison stationed “at Sellars Plantation” and warning of the continued Indian aggression. 18

Both of the forts on Patterson’s creek were abandoned in April 1757, the settlers having left the area, when Washington ordered their garrisons to move to the South Branch of the Potomac to protect settlers there.19 By then Captain Ashby had retired and the Rangers had been disbanded. The fort was subsequently used sporadically, but it doesn’t appear to have seen use after the close of the war in 1764.

Keller vs. Seller

Examination of the original handwritten documents show that Col. George Washington, Col. Adam Stephen, and Lt. Thomas Rutherford all very clearly wrote the name as “Seller” or “Sellar” rather than “Keller”. And James Genn’s 1748 survey (see image above) appears to show the name as “Charles Seller”. The grant for that survey, however, was issued to John Keller, son and heir of Charles Keller. And the 1749 road order refers to him as “Charles Keller” as well. I can’t explain this discrepancy, unless Charles Keller pronounced his name in a way that caused Englishmen to write it with an “S” rather than a “K”. Or perhaps he simply couldn’t decide whether or how to Anglicize his surname.

I note that something similar seems to have occurred with the name of Charles Keller’s cousin George Keller, whose name was on several occasions recorded in Frederick County record books as “Seller”. And Charles Keller’s son John Keller was recorded as “Sellers” in the 1782 and 1784 state censuses, as well as in other documents. The petition to establish the town of Frankfort spelled his name as “Sellers” while the town charter barely a month later spelled it “Keller”. All of the deeds for lots in town spelled it “Keller”. To add to the consternation, he signed the 1787 petition as “john Sellars” but signed two petitions in 1792 and 1793 as “john Keller”.

Charles Keller’s Death in 1756

The French and Indian war, had reached the area in 1755 and Indian attacks killed many settlers along the western reaches of the Potomac. Charles Keller is said to have been killed by Indians in 1756, although I could find no contemporary record of it. There are, however, numerous accounts of the murders of other settlers in the area in 1755 and 1756, sufficient to temporarily drive many residents away from the area.

One of the earliest records of his death is a statement made by a grandson, also named Charles Keller, to the author of an 1833 history that “Near [Ashby’s]Fort, Charles Keller was killed.”20 No date was given in that account but later, when his death was reported in several subsequent histories of the area, the year 1756 was added. That date appears to be likely, given the implication by Lt. Rutherford’s muster reports that Keller was alive in January 1756.

His family must have taken refuge back in Lancaster County. The 1758 poll list for Frederick County listed no Sellers and only one Keller — Charles Keller’s cousin George Keller who lived in the part of the county that became Shenandoah — as voters.

Excursis: “Seller’s Fort”

Northeast of Fort Ashby is a West Virginia historical marker commemorating “Fort Sellars” There is an historical maker for Fort Sellars “On land Washington surveyed for Elias Sellers in 1748.” This appears to be an historical error, perhaps generated by a family legend gone wrong in the retelling. The earliest mention of it in print that I found was a 1906 history that referred to a fort at the mouth of Pattersons Creek called Sellers Fort or Elias Sellers Fort, said to have been built on land surveyed for Elias Sellers on 1 April 1748 by George Washington. 21 This claim was repeated in subsequent publications, including Myer’s History of Virginia in 1915. But it is based on faulty information.

George Washington did assist James Genn in a survey on that date for land on which an Elias Sellars was living, but the surveyed land was fifty miles away on the south fork of the Potomac. (The only 1748 survey at the mouth of Pattersons creek was made by James Genn in November 1748 for Phillip Martin, to whom Lot 22 was granted.) No one named Elias Sellers seems to have ever lived anywhere near the mouth of Pattersons Creek. Nor does the name “Fort Sellars” appear anywhere within the George Washington Papers. Indeed, the stockade at the mouth of the creek was evidently not given a name. According to the Washington Papers it was a stockade protecting a storehouse at the mouth of the creek, built shortly after the nearby forts at Seller’s and Parker’s plantations.

The Washington Papers refer to it rarely and never by name. On 15 April 1756 Captain Ashby reported a confrontation with Indians at his fort and mentioned that later “I heard them attack the fort at the mouth of the Creek.” 22 When Washington reported the attack to the Governor he gave it no name but rather stated that “A small fort, which we have at the mouth of Patterson’s Creek, containing an officer and thirty men guarding stores, was attacked smartly by the French and Indians.” 23 A month later Washington instructed his paymaster to “come by Ashby’s, Cocks’s, and the detachment at the mouth of the Creek and also pay them off.”24

Several subsequent documents refer to Ashby’s and Cocke’s forts, but ignore the presence of a third fort at the mouth of the creek. Indeed, when the forts were abandoned in 1757 Washing referred only to “the two garrisons on Pattersons Creek.”25

Furthermore, the location was a poor one for a fort. On 21 December 1755, after Ashby’s fort was completed, Col. Adam Stephen wrote to Washington that “the valley at the mouth of Pattersons Creek [does] not extend above 800 yards from hill to hill… I really do not like the mouth of the Creek for our purpose [building a fort] nor any place in that neighbourhood on the Virginia side.”26 Consequently, the useful life of this fort was apparently just a few months. By May 18, 1756 Washington was ordering its stores moved to Ashby’s Fort.27

The myth of Fort Sellars appears to be either a historical misunderstanding or perhaps a family legend that was warped in the course of retelling. While there was an Elias Sellers fifty-odd miles away, there seems to be no evidence that he was ever in the vicinity of Pattersons Creek. A modern history of Virginia Colonial forts explains that “Fort Sellars” is mythical.28

Grant posthumously issued in 1779

The Indian depredations of the French and Indian War appear to have delayed grants in the vicinity of Pattersons Creek after the initial 15 grants of 1748 and 1749. Only two patents were issued for land along the nearly fifty-mile creek over the next sixteen years. Why Charles Keller’s patent was not issued along with his neighbors in 1749 is unclear, although the death of his neighbor McCracken apparently delayed the grant of Lots 17 and 18 until 1766.

On 1 June 1779 Lord Fairfax granted to “John Keller of Lancaster County in Pennsylvania, son & heir at law of Charles Keller dec’d” the 300 acres on Pattersons Creek known as Lot 16 — which was by then in Hampshire County — “bounded by a survey thereof made in November 1748 for the said Charles Keller by James Genn and forfeited by virtue of one advertisement issued from my office & recorded therein in Book N but another application of the said John Keller I have allowed.” 29 The survey was for a square parcel of 300 acres on both sides of Pattersons Creek. 139 acres, apparently the portion on the east side of the creek, were used by John Keller to lay out the town of Frankfort, more or less on the site of Ft. Ashby, which was charted by the Virginia General Assembly in 1787. For some time Frankfort was a booming town, being located on the busy road between Winchester and Wheeling. The post office later renamed the town “Alaska” and it is now known as “Fort Ashby”.

According to descendants, Charles Keller and his unknown wife had five children:

- John Keller (c1744 – 1805) The Fairfax grant establishes that he was the eldest son. He may have been the “John Sellers” enumerated in the 1782 and 1784 state censuses. 30 As noted above, in 1787 he was among the petitioners for the town of Frankfort, which was laid out on his land later that year. He died in 1805 while living in Frankfort, leaving seven minor children and a married daughter.

- Catherine (?-1831)

- Esther Keller (1747-1818) While there is no record which directly proves her parentage, a reasonable amount of circumstantial evidence exists. When John Keller died, three of her children31 were purchasers at the estate sale. Although Ester lived in Shenandoah County, she owned land in Hampshire County “near Frankford” which she mentioned in her will. A chancery case in Shenandoah County, establishes that George Keller, who had been in Shenandoah since about 1750, met the newly arrived Alexander Stocklager in 1769 and assisted in his purchase of land — his son George Keller Jr. testified in a later court case that George Keller Sr. was heard to say that Stockslager “was like a brother to him”.32

- Mary Keller (1747-1820)

- Daniel Keller (1753-1838)

- Appendix III: “Swiss and German Settlers in Lancaster County from 1709 to 1730”, in Daniel I. Rupp, A Collection of Upwards of Thirty Thousand Names of German, Swiss, Dutch, French and Other Immigrants in Pennsylvania from 1727 to 1776 (1927 edition), page 438. [↩]

- Pennsylvania German Pioneers, Ralph B. Strassburger and William J. Hinke, Lists 12A, 12B, 12C. [↩]

- This courtesy of the research of Evelyn Rowland. [↩]

- History of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, I Daniel Rupp (Published 1845), page 271. [↩]

- At least, no Keller appears in the grantee or grantor list prior to his death. [↩]

- Fairfax County Order Book 2, page 246. [↩]

- Northern Neck Grant Book R, page 217. [↩]

- Frederick County Order Book 3, page 120. [↩]

- The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745-1799, John C. Fitzpatrick, Editor. George Washington to George William Fairfax, October 23, 1755. [↩]

- Ibid. George Washington to Allan McLean, October 26, 1755. [↩]

- Ibid., George Washington to Richard Bacon, October 26, 1755. [↩]

- Ibid., George Washington to William Cocke & John Ashby, October 27, 1755. [↩]

- Ibid., George Washington to Richard Bacon, October 28, 1755. [↩]

- Nothing in Washington’s correspondence suggests that the site carried a name. [↩]

- George Washington Papers at the Library of Congress, 1741-1799: Series 4. General Correspondence, 1697-1799. John Ashby, Report on 2nd Company of Rangers January 12, 1756, and December 29, 1755. [↩]

- George Washington Papers at the Library of Congress, 1741-1799: Series 4. General Correspondence, 1697-1799. John Ashby to Henry Vanmeter and Thomas Waggener, April 15, 1756. [↩]

- Ibid., George Washington to Henry Peyton, May 12, 1756, two same date. [↩]

- Ibid., Adam Stephen to George Washington, August 1, 1756. [↩]

- Ibid.,George Washington to Adam Stephen, April 17, 1757; Mnutes of the Council April 16, 1757. [↩]

- Samuel Kercheval , A History of the Valley of Virginia (Originally published 1833, reprinted by EagleRidge Technologies, Inc. , 2009), page 95. [↩]

- Biennial Report of the Department of Archives and History…, Volume 1, (West Virginia. Dept. of Archives and History, 1906), pages 214-215. [↩]

- Washington Papers: John Ashby to Henry Vanmeter and Thomas Waggener, April 15, 1756. [↩]

- Washington Papers: George Washington to Dinwiddie, April 22, 1756. [↩]

- Washington Papers: George Washington to Alexander Boyd, May 18, 1756. [↩]

- Ibid.,George Washington to Adam Stephen, April 17, 1757. [↩]

- Washington Papers: Adam Stephen to George Washington, December 21, 1755. [↩]

- Washington Papers: George Washington to Adam Stephen, May 18, 1756. [↩]

- William H. Ansel, Frontier Forts along the Potomac and its Tributaries (McClain Printing Co., 1984). I note that Mr. Ansel’s chapter on Fort Ashby incorrectly identifies the landowner as John Sellar rather than Charles Sellar. [↩]

- Northern Neck Grant Book R, Page 217. [↩]

- That person was enumerated on a list which included residents of what became Hardy County, several miles from Pattersons Creek. It isn’t clear when John Keller moved back to Virginia. [↩]

- Jacob Stockslager, Joseph Reese, and Magdalena Stockslager’s husband Isaac Miller, all of whom lived in Shenandoah County [↩]

- Shenandoah County Chancery Case, Virginia Memory, Case No. 1793-001. The case documents clarify that George Keller Sr. knew Alexander Stockslager, though they lived quite some distance apart, presumably because Stockslager was married to his niece. [↩]